02/07/2020 - 23/07/2020

Can we turn the frictionless knowledge, tools and spaces, but also immaterial labour and cultural work of the world wide web, the 2.0, into new radical revolutionary productive spaces and practices, beyond the inflated idea of the “internet as a space of limitless possibility”?

What is the role and responsibilities of the art curators and art institutions in the virtual geographies with digital borders that frantically turn individuals into users, and commodify their interaction with the (un)limited choices of publicly accessible?

Hito Steyerl denotes that the gap between the two forms of representation—political on the one hand, cultural on the other—is a constitutive feature of communication technologies and social media. Julieta Aranda and Ana Teixeira Pinto, in the article Supercommunity (e-flux, 2017), go step further raising concerns if in fact the mechanisms that enable cultural participation simultaneously generate political exclusion?

Facing all of these questions and concerns, and with the hope to learn about more aspects and see different nuances to it, we are devoting our programme series What is Film? of 2020 to the exploration of the complex relation of the open and publicly accessible film art on the world wide web to the wider political and social questions. We conceive it as an act, a gesture, a program and a proposal for aesthetic education.

In practical terms, twice a week we will be sharing film art and related art forms on different themes, topics or issues, all of which are open and available worldwide.

Kumjana Novakova

PROGRAMME

INVENTORY 2.0.

Going deeper into the present moment, the first theme within What is film? Inventory 2.0 is devoted to the struggle of the Black people. Acknowledging the lack of the knowledge on the complexities of blackness, we would like to reject the idea of the struggle as statistics and contribute to the greater present political shift that turns metrics into something more human, more vivid, more personal.

Thus, we share information on a publicly accessible film artwork.

CinemAfrica, an independent cultural organization devoted to celebrating African and African Diaspora cultures and people, will be streaming free on its website I Am Not Your Negro by Raoul Peck (2016), looking at the novelist, playwright and essayist James Baldwin.

“Baldwin could not have known about Ferguson and Black Lives Matter, about the presidency of Barack Obama and the recrudescence of white nationalism in its wake, but in a sense he explained it all in advance.” writes A.O. Scott in the New York Times (Review: ‘I Am Not Your Negro’ Will Make You Rethink Race, Feb 2, 2017).

For the ones who are interested in extending beyond the key aspect of the writer’s life and work that Raoul Peck’s leaves out: his sexuality, we would recommend a discussion between him and Audre Laurde published in 1984 and available here.

The second theme we are pinning on the Inventory 2.0 is: archives.

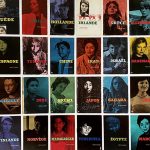

Considered by many as one of the most prominent and interesting filmmakers working with archives nowadays Jean-Gabriel Périot is a filmmaker whose films confront us with the possibility of different readings of the historical archives, and can be placed at the crossroads of documentary, animation and experimental. Strongly politically and socially engaged and intense, almost all of his work calls into question unjustly established social hierarchies, global and local economic dependences, institutionalized violence, people-to-people violence, abuse of power, and war.

His films have been screened and awarded around the world, both within cultural and artistic platforms and in public spaces, sparking debates and a sense of urgency in action, questioning generally accepted actions in historical and contemporary narratives.

Another aspect of Périot’s work especially interesting for the Inventory 2.0 is his dedication to publicly accessible art: most of his films are available to see online, regardless of the fact that numerous festivals and film platforms are programming his work inside cinemas and galleries.

Our first recommendation, linking it to our previous theme is his film The Devil, edited to the sound of the powerful French band Boogers, the images enter the struggle of the African-Americans in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Devil, Jean-Gabriel Périot, France, 2012, 7’ – available here.

The Devil, Jean-Gabriel Périot, France, 2012, 7’ – available here.

The second recommendation is for a work based on archive photography – as much as 600 photographs capture the Gembaku Dome in Hiroshima since 1915 to present days, layering pain and violence in survival.

Nijuman no borei (200 000 phantoms), Jean-Gabriel Périot, France, 2007, 10’ – available here.

On a different from the archive works, is our final recommendation – There is Joy in This Struggle – a work commissioned by the Paris Opera on the occasion of their 350tieth anniversary.

Périot’s grabs the chance to speak up of economic uncertainties and deep divisions in the society on the background of the pleasures of music.

There is Joy in This Struggle, Jean-Gabriel Périot, France, 2017, 22’ – available here.

Assemblage – Cambridge Dictionary (US/əˈsem·blɪdʒ/), noun

Assemblage – Cambridge Dictionary (US/əˈsem·blɪdʒ/), noun

A collection of people or things that are brought together for some reason.

in ART:

An assemblage is also a work of art that is made of different things put together.

The third theme on the Inventory 2.0 comes both as a method of work and subject of study: assemblage.

Thinking within the idea of assemblage, it urges us to reject to think of film as a simply, singular unity, a liner experience, a closed text with fixed meaning.

In fact, in the assemblage film form is imposed through a temporal chain that joins separate and most importantly seemingly unrelated images. Thus, as a result, meaning arises from the proximity that is created – on the opposite of the usual dependence on the metaphor.

Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) identified with no school of filmmaking and never worked on the theoretical frame of the medium of film. Although he was better known as an artist, best-known for his boxes in which he arranged various objects and materials, he surely marked filmmaking by fascinating and influencing both his peers and newer generations of artists.

Cornell appeared to be an oddity, an “outsider”, avoiding social contacts except on his own terms; some saw him as “weird” when it came to relationships with women whom he worshiped at a distance. Always single and virtually housebound, he used art to turn female celebrities into unreachable, slightly androgynous icons. (Brink, 2007).

Such was his first film: Rose Hobart, built entirely from the footage of East of Borneo, a 1931 jungle B-film, that Cornell turns into a film about an actress that supposedly preoccupied his hermetic world.

The legend says that many surrealists attended the premiere of his first film Rose Hobart (USA, 1936, 20’), at the Julian Levy Gallery in NYC, as many of them had come to New York to attend the opening of the first MoMa’s exhibition featuring Surrealist art Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. In the audience was also Salvador Dalí, who became extremely agitated during Cornell’s screening and overturned the projector. “My idea for a film is exactly that, and I was going to propose it to someone who would pay to have it made….,” he reportedly told Levy. “I never wrote it or told anyone, but it is as if [Cornell] had stolen it.” (Salvador Dalí, as quoted in Brian Frye, “Joseph Cornell 1903–1972).

Rose Hobart (USA, 1936, 20’) is available on the UBU WEB.

“All great fiction films tend toward documentary, just as all great documentaries tend toward fiction . . . He who opts wholeheartedly for one necessarily finds the other at the end of his journey.”

“All great fiction films tend toward documentary, just as all great documentaries tend toward fiction . . . He who opts wholeheartedly for one necessarily finds the other at the end of his journey.”

Jean-Luc Godard

Traditional nonfiction filmmakers nowadays often present their work in art galleries and museums around the world, while artists increasingly exhibit their work at film festivals and cinemas. Obviously, the lines between art and film blend or disappear, as does the blurry line between fiction and nonfiction. Hybridisation, novelty, dissent, heterodoxy and amalgamation have been crucial to the advancement of the contemporary art film, regarded by many as docu-fiction – that is filmmaking that weaves together traditional nonfiction filmmaking with traditional fiction filmmaking.

The contemporary resonance and immediacy of some of the formal characteristics of the docu-fiction films—their indeterminacy, hybridity, sincerity, liveliness—has led us to share the work if a filmmaker and an artist whose work doesn’t fall inside of any of the traditional boxes and allows itself to be defined as all of the previous inclusively, and none of the previous exclusively.

Zoe Beloff (1958, Edinburgh) is an artist and filmmaker. She studied art at Edinburgh University and in 1980 moved to New York to study film at Columbia University. She works with a wide range of media including

film, projection performance, installation and drawing. Each project aims to connect the present to past so that it might illuminate the future in new ways. Beloff’s projects have been presented internationally.

A Model Family in a Model Home takes as its starting point notes for a film by Bertolt Brecht. Brecht was inspired by an article he read in Life Magazine in 1941 about a farm family who win a week’s stay in a model home at the State Fair. The drawback was that the home was open to the public twelve hours a day. He imagined what happened when everything went wrong.

Exile.

The philosopher Walter Benjamin and his friend the playwright Bertolt Brecht spent time together in exile from Nazi Germany in the1930’s. This film imagines that they are still in exile in New York 2017. In the intervening years they have changed because in the contemporary world, refugees and victims of racism look different. Brecht is Iranian. Benjamin is African American. Unfixed, oscillating between their time and ours, Brecht and Benjamin reveal what has been buried in our own history, making connections between fascism in New York in the1930’s and its manifestation in the Trump era.

Different from both narrative or fiction as well as documentary filmmaking, while closely related to literature and philosophy, and characterized by a loose, fragmentary, open-ended reflection build upon constant tension of several discursive modes, the essay film advances the aesthetic possibilities of cinema. Neither a genre, nor a form, the essayistic language is the film of the space of the inside: searching, questioning, protesting, like passages to the uncertain and the unseen, through the poetics of the distant we reach weightlessness and nearness.

Different from both narrative or fiction as well as documentary filmmaking, while closely related to literature and philosophy, and characterized by a loose, fragmentary, open-ended reflection build upon constant tension of several discursive modes, the essay film advances the aesthetic possibilities of cinema. Neither a genre, nor a form, the essayistic language is the film of the space of the inside: searching, questioning, protesting, like passages to the uncertain and the unseen, through the poetics of the distant we reach weightlessness and nearness.

While the practice of the essay filmmaking is characterised by considerable variation and thus the impossibility to be boxed due to its ever-growing inbetweenness, its origins are closely related to “the best-known author of unknown movies”, Chris Marker.

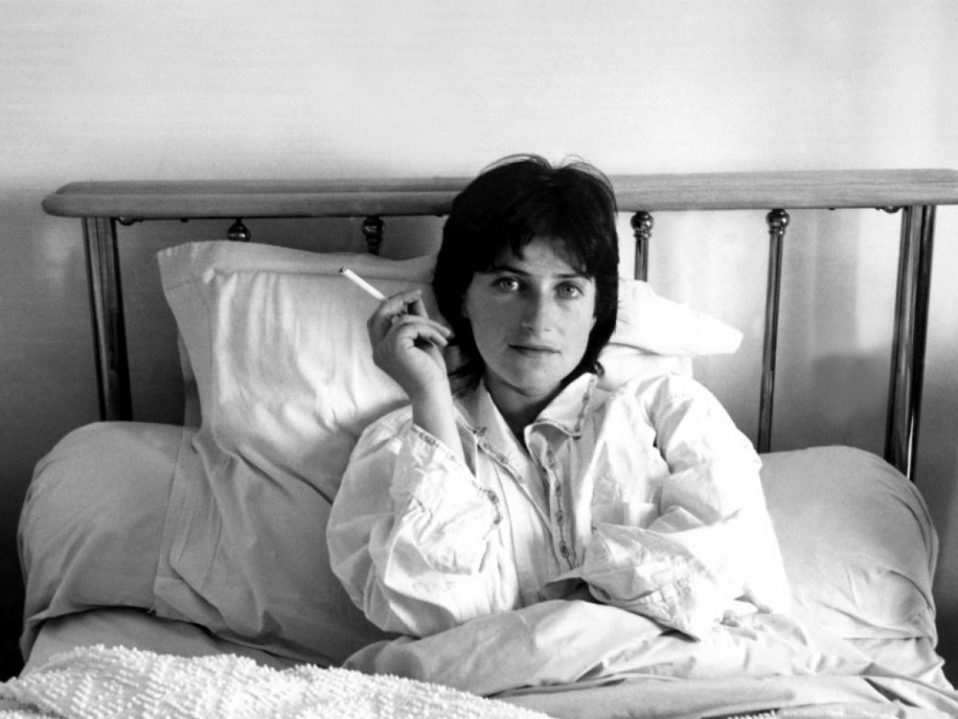

This posting however is devoted first to Hélène Châtelain, as not only enough has been said about Chris Marker, but also we deeply believe that he would be flattered to act as an introduction to her work. Widely known as the actress of La Jetée, Hélène Châtelain’s life was devoted to creation – an actress, a writer, a filmmaker, a voice for the oppressed, a bridge for the East.

“Workers of the world, go to the depths of your soul for only there will you find the truth.” – she will share the words of Nestor Makhno, the anarchist and communist from Ukraine, whose life she will reconstitute from his writings, Soviet propaganda films, reactions of workers today and the memory he left in the heart of his people in Huliai Polye.

The film is available through the Internet Archive here.

While our next post will be completely devoted to Chris Marker, as an homage to Hélène here we share his La Jetée.

Because I know that time is always time

Because I know that time is always time

And place is always and only place

This is the epigraph to the English-language version of Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, when it was released for distribution in the United States in 1982. The epigraph to the original French version of Sans Soleil is taken from Racine’s second preface to Bajazet – his only work rejecting mythological, biblical or historical subjects, as the Turkish tragedy is set in contemporary seraglio (harem). The epigraph reads: we may say the respect that we harbor for heroes increases in proportion to their distance from us. These three accents from the two epigraphs – on time, place and no-heroes – sublimes somehow Marker’s gaze in all of his work in all mediums and across all life periods.

As the previous text and posting on Hélène Châtelain briefly introduced Marker and the essay film, thus we will restrain from theoretical remarks this time. Instead, we will try to inspire you to look for, and hopefully think about poetry of time and find your own Chris Marker. You will meet a cine-novelist, filmmaker, writer, photographer, traveler. A time-traveler capturing future memories in ciné-romans. A cat-lover. Because a cat is never on the side of power.

“This is the story of a man, marked by an image from childhood.” And Sans Soleil takes us to a journey… A first-person account set in a film borrowing Mussorgsky’s title of song cycle (1874), this time composed of diary-like letters of yet another alias of Chris Marker – Sandor Krasna – introduced as a “free-lance cameraman” travelling to “two extreme poles of survival”, Japan and Africa.

The moment we set foot in the world of appearances of Japan, we enter a kind of a disembodied consciousness… And, our own memories start reaching us. In a film about somewhere else.

A version merging both French-version and English-version epigraphs, narrated in English by Alexandra Stewart, is available through the Internet archive here.

For a beautiful personal note on Sans Soleil, we recommend you to look at Chris Marker’s Letter to Theresa – Behind the Veils of Sans Soleil

For breath-taking portraits during demos, we recommend you to look at this image gallery of Sandor Krasna on Flickr

Direct, funny, fast, insightful, intuitive, clumsy, smiling, capricious. Chantal Ackermann is the author who marked auteur film after the French New Wave. Film scholar Gwendolyn Audrey Foster considers her “one of the most important filmmakers of the late-20th century, whose films have had a profound impact on feminist discourse within the cinema, and within avant-garde film and video art at an international level.” (Senses of Cinema. Akerman, Chantal. February 2018, Issue 86).

Direct, funny, fast, insightful, intuitive, clumsy, smiling, capricious. Chantal Ackermann is the author who marked auteur film after the French New Wave. Film scholar Gwendolyn Audrey Foster considers her “one of the most important filmmakers of the late-20th century, whose films have had a profound impact on feminist discourse within the cinema, and within avant-garde film and video art at an international level.” (Senses of Cinema. Akerman, Chantal. February 2018, Issue 86).

She will make her first film at the age of 18 – “Blow Up My Town” (Saute ma ville, 1968, 13’) – and the need to literally blow up the current decency will remain in every next film of Chantal, until her death in 2015. She will articulate the female gaze and female desire in film – courageously, openly, self-critically.

We close the Inventory 2.0 programme with a recommendation to listen to, read and watch Chantal.

Starting from her room – “The Room“ (La chambre, 1972, 11′) which is integrally available on E-flux (E-flux, May, 2020), you can read the interview of Nicolas Brenez from the French Cinematheque with Chantal made in a period of one month in the summer of 2011, and watch the conversation with Chantal in Venice, also in 2011.

To make ‘art’ is usually wonderful. The art market is another thing. It’s often tied to power, to the phallus – but not always. Chantal Akerman.